Monthly Archives: June 2009

June 30, 2009

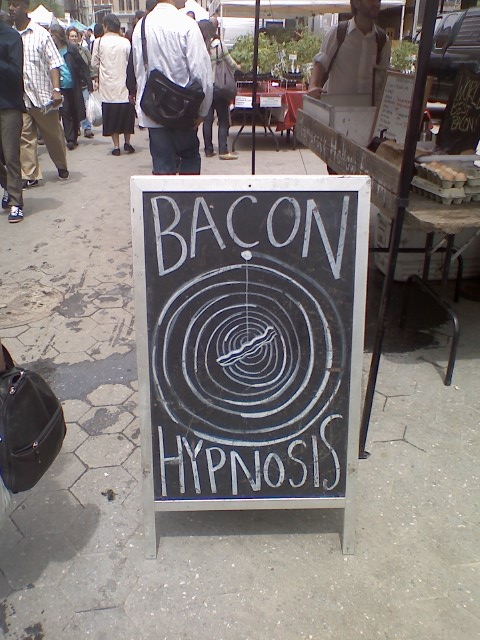

This may be the best idea anybody has ever had.

Unfortunately, though I looked everywhere, I couldn’t find the practitioner, which leads me to believe either that he or she was killed by unhypnotized bacon shortly after erecting this sign or that there was in fact never any bacon hypnosis at all and this was a cruel joke played on me and the other market visitors by an uncaring fate.

June 29, 2009

In tenth grade Biology, when we dissected fetal pigs, I named mine Benito so that it could be a fascist pig.

June 27, 2009

I once had a job with which I became so disillusioned that one day, when my boss came back from lunch, I actually said to her, “Um, somebody called for you while you were out, but I forgot his name and I didn’t write down the phone number.”

I kept the job for another three months.

June 25, 2009

So the other night I watched the movie of The Count of Monte Cristo on pay-per-view. As I’ve said before, recently, The Count of Monte Cristo is my all-time favorite book, because it is basically 1,100 pages of revenge, which warms the cockles of my cold and bitter heart. The problem with adapting it for the screen (or for the stage, for that matter, which I once attempted, with disastrous results) is that what makes the book so fabulous is the inexorable slowness of it. He takes 800 pages to ruin the lives of everybody who framed him. It simply isn’t possible to convey this in less than, oh, say, six or eight hours. Apparently there is a French mini-series but I’m scared to see it because it stars Gérard Dépardieu.

In any case, I watched the movie not in hopes that it would be a particularly good adaptation, but simply because I enjoy a good costume drama.

What I do not enjoy is when people in a costume drama call each other the wrong thing. Everybody in the movie kept on calling the Count of Monte Cristo “Your Grace,” and it made me want to claw my eyes out.

“Your Grace” is what you call a duke or, in some cases, a bishop.

Nobody would everhave called the Count of Monte Cristo “Your Grace.”

Yet movies and TV shows get this wrong all the time. I can’t think off the top of my head of a royal costume drama I’ve seen in which people didn’t fling “highness”es and “majesty”es around indiscriminately as if they were water balloons at summer camp.

It’s not that hard, people.

In addition to the fact that forms of address have changed over the centuries, there’s a great deal of flexibility built into the system, so royal and noble tempers can be appeased and nobody’s head gets chopped off. In this case, there’s even more flexibility, since people seem to be speaking English on screen when we understand that they’re actually speaking French, so there are two different aristocracies to deal with and a translation. But it’s one thing to write a script in which people call a bishop “Your Grace” when strictly speaking they should be calling him “Your Excellency”; change the country he’s from and/or the country he’s in and you might be right after all. But for people to slouch around calling counts “Your Grace” is as realistic as people addressing the mayor of their town as “Mr. Ambassador.”

Counts are actually a particularly tricky case, since although in English we have the word “count” there are in fact no counts in England; the corresponding English rank is earl. The wife of an earl is a countess. An earl is addressed as “My Lord,” a countess as “My Lady.” So presumably one could get away with calling the Count of Monte Cristo “My Lord.” In French the usual form of address is “Monsieur le Comte,” so that would be fine, although translating to English and calling him “Mister Count” would just be weird. (The Count of Paris is addressed as “Monseigneur le Comte,” but I have yet to see him in a movie.) It’s also possible to address a count as “Your Excellency” (in French “Votre Excellence”).

Notice that “Your Grace” does not appear in the list of options.

Herewith, therefore, a brief and not comprehensive discussion of how to address various people in English. (These are all to be used the first time one speaks to the person in question. After that you just say “you” (or “sir/ma’am”) and drop the title occasionally into the conversation depending on how obsequious you want to be.)

Kings and queens are addressed as “Your Majesty.”

Their prince and princess children are addressed as “Your Highness,” unless they are directly in line for the throne, in which case it’s “Your Royal Highness.”

Emperors and empresses are addressed as “Your Majesty” but referred to in the third person as “His/Her Imperial Majesty.”

The pope is addressed as “Your Holiness” or “Holy Father.”

Cardinals are addressed as “Your Eminence.”

Bishops are addressed as either “Your Excellency” or “Your Grace” (depending on the place of their bishopric, but screenwriters have enough to worry about that I feel they ought not to be required so to extend themselves on research).

Pretty much everybody is addressed as “My Lord” or “My Lady.” This includes barons and baronesses, marquesses and marchionesses, viscounts and viscountesses, and plain old lords and ladies. There are a lot of complicated rules about the older and younger children of all of these people, which I won’t go into here.

Other possibly useful information:

When the king or queen of one country writes to the king or queen of another country, the salutation is “Sir My Brother” or “Madam My Sister,” unless the two rulers are actually related, in which case that gets stuck at the end; e.g., “Sir My Brother and Father.” (Let’s just not touch the incest implications here. But all those royal families are inbred anyway.)

When a king or queen writes to the president, the correct closing is, shockingly, “Your good friend.”

When the Holy Roman Emperor (you never know when that’ll come back) speaks of himself to someone else, he says “Ma Majesté.”

And one other thing about The Count of Monte Cristo, the movie: at one point, the hosts of a party that the count has been invited to see another couple there and say “what are they doing here?” Then it becomes clear that the count has invited the second couple to meet him at the party.

The Count of Monte Cristo would no sooner have issued a second-hand invitation than he would have chopped his own arms off.

And the next time I hear somebody address a princess as “Your Majesty” I won’t be held accountable for what happens.

(I will admit the infinitesimal possibility that I’m wrong about some of the above particulars, though I don’t think so; if I am, though, “Your Grace” for the count is not one of them.)

June 22, 2009

I wrote this for an upcoming issue of HX magazine celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Stonewall riots. It’ll be part of a section in which several people prognosticate on the future of the gay community and its culture. My thoughts on the issues involved are somewhat more complicated than shows here, and I’m leaving a lot of things out, but I only had 350 words, and this communicates the gist of what I wanted to say.

Here are Harvey Milk’s words, familiar to many of us from the movie Milk:

“Without hope, not only gays, but the blacks, the seniors, the handicapped, the us-es, the us-es will give up. And if you help elect, to the central committee and other offices, more gay people, that gives a green light to all who feel disenfranchised, a green light to move forward.”

In the future, the LGBT community will actually live by these words rather than simply paying lip service to them. We will understand that “us” has to be not just gay people but all the disenfranchised—black people, disabled people, Asian people, the poor, the homeless—that when any of them suffer yet another indignation, it hurts us too. We’ll realize that, as we sit at our computers (which we own) in our houses (which we own) after coming back from our jobs (which we have), if we don’t turn at least some of our attention to those of us in far worse shape than we are, we’ve missed half of what Harvey Milk was trying to say.

When there’s another Proposition 8, we’ll actually take out ads in black newspapers and put up posters in black neighborhoods and show black people in our television commercials, instead of ignoring them, and this time the proposition will fail.

Our support for the transgendered will go beyond adding a T to the names of our organizations. We’ll be racially integrated not just in the ad pages of our periodicals but also at our dinner parties.

We’ll learn that those who stand against us may be more complicated than they appear: That Isaiah Washington, before he shocked us with his bigotry when he called T.R. Knight a faggot, had played one of the most memorable characters in gay film, Kyle in Spike Lee’s Get on the Bus, and written an article for Essence decrying homophobia in the black community. That Rick Warren, whose participation in President Obama’s inauguration we protested because of his horrific slanders against us, has almost singlehandedly forced evangelical Christianity to start paying attention to the environment and to world poverty.

In short, we’ll get what Harvey Milk was trying to tell us.

June 19, 2009

Since I’ve made a few posts about my dad and the Supreme Court lately (with the notable exception of yesterday), here’s a piece he wrote a few days ago.

While Supreme Court watchers have been sparring over whether Judge Sonia Sotomayor once said something racist, the Court itself has been considering whether to rip the heart out of the most effective civil rights law ever passed.

The endangered law is Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the showdown will come in the next two weeks when the Court decides the case of Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No .1 v. Holder, sometimes nicknamed the MUD case.

Based on the Justices’ questions at the oral argument in April, the Court seems to be evenly split. In the end, it may be outgoing Justice David Souter, in his last act as a Supreme Court Justice, who finds a surprising way to save the law.

The question for the Supreme Court to answer is not quite what many people think it is. Many think the question for the Court is is simply whether the protections of the law are still needed, but that was actually the question for Congress to answer. Congress, which has the responsibility to enforce the guarantees of the 14th and 15th amendments, answered that question in the affirmative only three years ago. After extensive hearings and a 15,000-page record, Congress voted to renew Section 5 in 2006 by bipartisan margins of 390-33 in the House and 98-0 in the Senate. President Bush signed the bill in a Rose Garden ceremony. At this stage, the question for the Justices is not whether they themselves believe the protections of Section 5 are still needed, but whether Congress acted reasonably or was so far off the wall that its action was unconstitutional.

The difference between the two questions may decide the case. If the Court focuses on whether Congress acted reasonably, it will probably uphold the law. If the Justices—or a majority of them—believe they can override Congress based on their own views about what protections are still needed, the outcome is anybody’s guess.

Whether Section 5 is still needed is central in the MUD case because it is a temporary remedy. As part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that broke the back of disfranchisement in the South by outlawing literacy tests, Section 5 was included to protect the gains and prevent backsliding. For states with the worst history of discrimination, Section 5 set up a special streamlined procedure to block new, potentially discriminatory voting rules. It acts as a “temporary injunction,” suspending all new voting rules until they get federal approval (“pre-clearance”). This is in contrast to the ordinary procedure of allowing new rules or laws to be enforced unless and until someone goes through the difficult, lone and expensive process of bringing and winning a lawsuit. As Chief Justice Earl Warren said in 1966, Section 5 was adopted “to shift the advantage of time and inertia from the perpetrators of the evil to its victims.”

Since its adoption, Section 5 has blocked thousands of discriminatory voting rulers—from major changes like gerrymandering designed to keep county councils all white, to smaller ones like a last-minute move of a polling place to a remote location inaccessible to black voters. Many of the discriminatory changes blocked by Section 5 have been very recent. In one example, discussed in the oral argument in the MUD case, a Texas county tried to minimize black voting in a special election by scheduling it during the vacation time of the local black college.

The stringency of the remedy, and the formula that covered only certain states, were based on a massive record before Congress. The Supreme Court held in 1966 that Section 5 was well within the constitutional power of Congress to enforce the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments.

Since then, Congress has revisited the continuing need for Section 5 on four occasions, the most recent being the 2006 renewal. Each time it has concluded that the law is still needed to block voting discrimination. In the past, the Supreme Court has rejected constitutional challenges to the law and has upheld Congress’s judgment.

The question now is whether this Supreme Court will defer to the judgment of the legislative and executive branches or whether the Court will substitute its own contrary belief about what laws the nation needs.

The Court has gone down this road before, and the result was an unmitigated disaster. That was in 1883, in the aftermath of the Civil War and Emancipation, when the Court struck down a civil rights law that Congress thought was necessary but the Court thought was not.

Then as now, the question was how long civil rights laws would be needed to prevent racial discrimination. Congress passed a series of protective laws including the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which outlawed discrimination in restaurants, theaters and other public places. The need for the law was shown by massive evidence before Congress of systematic and violent resistance to the rights of the freedmen.

But when the law came before the Supreme Court in United States v. Stanley (also called The Civil Rights Cases), the Court made its own political judgment about what laws were needed and for how long: “When a man has emerged from slavery, and by the aid of beneficent legislation has shaken off the inseparable concomitants of that state, there must be some stage in the process of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen, and ceases to be the special favorite of the law.”

Congress had made the decision that the time to let up was “not yet,” but the Court on its own said the time was “now,” and held the statute unconstitutional. Justice Harlan accused the Court of turning the 13th and 14th amendments into “splendid baubles, thrown out to delude those who deserved fair and generous treatment from their nation,” but he was a lone voice in solitary dissent. The 1883 case paved the way for the world of Jim Crow, even before the decision in Plessy v. Ferguson.

(In a foreshadowing of current events, the opinion in The Civil Rights Cases was written by the Justice (Joseph Bradley) who six years earlier had cast the deciding vote to pick the President of the United States after the 1876 elections were contested because of disputed votes in Florida (!) and two other states.)

More than a century later, the same concept of judicial supremacy was being heard at the oral argument in the MUD case, especially from Chief Justice Roberts and Associate Justice Scalia.

The Chief Justice compared the problem of voting discrimination to a joke about a man using an elephant whistle to keep imaginary elephants away—a comparison that makes sense only if you believe voting discrimination is nothing but a figment of someone’s imagination.

Justice Scalia derided the strong congressional vote, saying the Senate’s 98-0 vote made him suspicious (apparently forgetting that his own nomination as a Justice was confirmed by the same 98-0 vote).

The comments of these Justices contrasted sharply with their oft-professed view that judges should defer to policy choices of the legislative branch, and with their criticism of so-called “judicial activism” of earlier courts. But whereas earlier decisions were “active” in overriding Congress to enforce the guarantees of the Bill of Rights and the constitutional promises due process and equal protection of the law for every citizen, the new judicial activism of the Chief Justice and Justice Scalia seemed to be enlisted in the cause of resisting Congress’s efforts to make constitutional rights real and effective.

By the end of June, all these speculations will be answered in the Court’s decision.

Which is where Justice Souter comes in. Early in the argument, he began questioning whether the MUD district had “standing to sue” and whether there was an actual “case or controversy.” These requirements must be met for any case to be in federal court, and they depend on proof from the plaintiff—here the MUD district—that it has a real dispute as opposed to a theoretical disagreement.

Justice Souter’s questions are critical because the MUD district, while arguing that it shouldn’t be covered by Section 5 at all, doesn’t have a voting rule it is seeking to enforce. And it may not ever have one, since its elections are all conducted by its county—which not only supports Section 5 but has filed a brief in the Supreme Court saying so.

If the Supreme Court dismisses this case for lack of MUD’s standing to challenge the constitutionality of Section 5, it will not end the controversy over the law, but it will leave it for another day. And if Justice Souter leads a majority of the Supreme Court to a decision saving Section 5, even for a time, it will be a fitting end to a fine career.

June 18, 2009

N.B.: The first part of this entry was originally posted on July 22, 2004. I repost it now so as to be able to give you an update. Also, if you find the post and/or the update amusing, I hope you’ll consider buying my book.

One of the many things I like about my relationship with E.S. is that the sex is consistently fabulous. However, he being a first-year resident at a hospital, there are perforce occasional periods during which we don’t see each other for a while; at such times, I have not infrequently performed certain endorphin-releasing activities on my own. On these occasions I have been content to use as visual aids the small stash of pornographic videos I collected in the early 1990s, when my taste in such things seems to have been formed. The haircuts are most unfortunate, but I find the body shapes on the whole more pleasing than those in videos being made today.

However, a couple weeks ago, I ordered a new video from the folks at TLA (that link is safe for work, by the way, though certain pages on the site are most certainly not). The detailed review of the movie on the web site indicated that it contained a scene involving a fairly uncommon sexual activity that I find particularly arousing. The one or two times I’ve actually participated in this activity, the experience has been unerotic and, in fact, somewhat distasteful, so I have no plans to try it again; nevertheless, the idea of it remains exciting.

A few days later, the TLA package arrived–on a day, it so happened, when E.S. was going to be on overnight call at the hospital, so I had ample time to enjoy my purchase. The film started off promisingly enough, with someone who could conceivably be a high school student if high school started at age 26 entering what could conceivably be the principal’s office if principals’ offices were badly-lit rooms empty of all appointments save a curiously bare desk. Someone who could conceivably be the principal entered and began to castigate the student for spending so much time sucking cock that his grades were suffering; the scene progressed satisfyingly if predictably from there to its inevitable conclusion. The next scene had similar credibility issues but was equally fulfilling–from a mathematical perspective, in fact, it was twice as fulfilling, as it had twice as many people in it.

The third scene was the one in which, according to the review, the activity for which I’d purchased the movie occurred. I watched as the school janitor (the first well-cast role in the piece) chanced upon some contraband material in a student’s locker and took the student down to the boiler room to punish him. Strangely enough, these two were inclined to behave in the the same manner as the principal, the detainee, the athlete, his coach, and his two teammates; however, after a while they stopped doing that, and seemed to be preparing to do something else. Breathless with, um, anticipation, I awaited eagerly the extensive scene the TLA review had described–

–and got about thirty seconds of the tail end of it, after which the two actors moved on to something else.

I went nearly mad with shock and dismay. After finishing the task at hand–not nearly as pleasant an accomplishment as I’d expected it would be–I called up the web page and reread the review, thinking that perhaps my wishful memory had played me false. But no: right there in black and white–with full color photographs–was a description of events that did not take place in the movie I had bought.

Clearly this was an untenable state of affairs. But resolving it was going to be tricky. After all, the all-but-omitted sexual activity was just enough beyond the pale for me not to feel comfortable calling the company and identifying myself as an aficionado in an effort to correct the error. True, I could simply return the movie for a refund, but that would destroy any chance I had of actually obtaining the movie I’d thought I was buying, which was of course the most desirable outcome.

Eventually I hit upon the brilliant solution of sending TLA an e-mail into which I pasted the relevant paragraphs from their own review; I bolded the parts that had been left out and asked them to let me know how I could get a copy with those parts put back in. That way I didn’t even have to refer to the damning sex act by name–whoever got the e-mail couldn’t very well turn his nose up at his own company’s language. Pleased as punch with myself (and full of endorphins, however unfulfillingly released), I went to bed.

And woke up the next morning to find an e-mail in my inbox saying, “Pardon the inconvenience, but please contact us by phone to resolve this issue.”

Fuck.

So today, when I got home from the gym, I called them.

“Hello, this is Nick,” said the guy on the other end of the phone. “How can I help you?”

“Well,” said I, “I recently bought a video from you that seems to have part of a scene missing. There’s a scene described on the web site that isn’t all there.”

“Oh?” he asked, concern filling his voice. “What was the movie?”

“It was [Name of Movie],” I answered, after which I gave him my order number.

“So you say there was part of a scene missing?”

“Yes.”

I was silent, hoping against hope that Nick, wonderful Nick, cute, understanding Nick, would know exactly what the problem was without my having to explain it.

“What was missing?” he asked.

Hateful, ugly Nick.

I wondered desperately if Nick spoke French. My French is good enough to return a movie.

Then I realized I didn’t know the name of the activity in French.

“Um,” I continued in English, “well, there’s a [name of activity] scene, and only part of it appears on the disc.”

“Yes, I can see that there’s a [name of activity] scene. But what part of it is missing?”

I attempted to develop spontaneously the ability to project my thoughts into the minds of others, so as not to have to continue this conversation, but I failed.

“Do you have e-mail?” I asked wildly. “I could just e-mail you a description of what’s missing.”

“If you send an e-mail it won’t be dealt with properly.”

I thought about becoming an ex-gay so as to have an excuse not to own this movie, but realized quickly that I like getting fucked too much to become an ex-gay. There was nothing for it but to, um, plow ahead.

“How about if I just read you the section from your web site that describes the part that’s missing?”

“Okay.”

“Okay, so see where there’s the paragraph that ends, um, ‘A willing Chad takes stream after stream of Matt’s impressive load in the face without flinching’?”

I considered traveling back in time and preventing human beings from developing the power of speech.

“Yeah, I see that.”

“Okay, well, the next paragraph, the one that starts, ah, ‘Next up is the adorable Billy, who [performs the activity in question on] Eric like there’s no tomorrow,’ nothing described in that paragraph is on the disc I got. And then the first sentence of the next paragraph, the one that says, ‘Then we’re treated to the delightful sight of Eric [performing the activity in another way,]’ that’s not there either. I only have the scene starting from the next sentence, ‘To finish things off before going in for the kill, Billy [performs the activity in yet a third way.]'”

By this point I was strangling with mortification.

“Hmm,” said Nick. “Okay, let me go check with my manager, who’s in charge of ordering these.”

During the two minutes during which I was on hold, I started to check out airfares to Siberia, where I could drown myself in Lake Baikal, the largest freshwater lake in the world. Unfortunately, Nick returned before I’d been able to finalize my purchase.

“My manager says we must somehow have sent you the retail version. He says the [activity] scene is really quite extensive in the director’s cut. Let me give you a return authorization number so you can send the disc back. As soon as we get it, we’ll ship you out the correct version.”

“Oh, great,” I said tearfully, grateful that I would soon be able to hang up and instantly repress all memory of this conversation.

“I’m so sorry for the trouble. Is there anything else I can do for you today?”

“No, thank you.”

And it was over. Slowly–oh, so slowly–but surely, the excess blood began to drain from my face and redistribute itself throughout the rest of my body. My breathing started to return to normal, and I thought, Well, at least I know I’ll never be that embarrassed ever again in my entire life.

Then I realized that my door was open and my brother’s houseguest had been sitting on the couch in the next room the whole time.

Update, June 18, 2009: The replacement video that TLA sent me was similarly truncated, as was the replacement replacement video that TLA sent me. A year or two later I tried again, figuring that perhaps they’d just had a bad batch of DVDs. Of course I couldn’t find the replacement replacement video so I had to buy it again. Imagine my lack of surprise when the [activity] scene was missing the exact same parts. Then when I started downloading torrents I naturally found a torrent of the video, but when I watched the file—which took several days to download completely—it was the regular version, not the director’s cut, so there was even less of the [activity] scene than before. The second time I downloaded it exactly the same thing happened. Then, a few months ago, I found the studio’s website and signed up, credit card and all, and paid to rent the movie for 48 hours, but the file I downloaded wouldn’t open. This turned out to be, as I found out when I e-mailed the studio (I didn’t have to speak with anybody this time; thank God for small favors), because I hadn’t read the platform requirements on the website, and the download-for-48-hours feature only worked on PCs. The customer service representative who explained this to me (the embarrassment I was saved by the representative’s not being Nick was made up for by the representative’s being a woman) wrote that she’d credited me for an hour of the watch-now-online (streaming) feature. The scene turns out to be pretty fucking impressive, but the two times I’ve watched it I’ve been so worried about using up as little time as possible that I might as well have been watching an episode of Flip This House for all the good it did me.

The universe is obviously trying to tell me something.

I’m not listening.

June 16, 2009

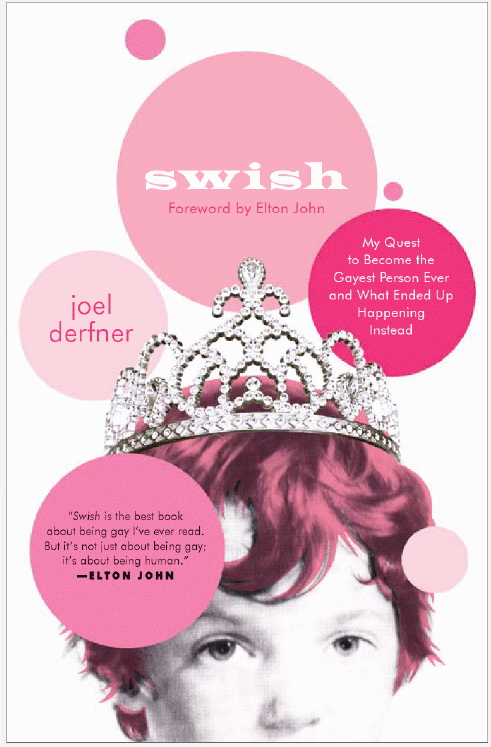

It was just over a year ago that my book Swish: My Quest to Become the Gayest Person Ever was released, and I am now at liberty to reveal a piece of information about which I have heretofore held my tongue:

Swish has not sold as well as my publisher hoped it would.

I have no idea what this means in terms of actual copies sold, since this information is more difficult for an author to get hold of than, say, the Golden Fleece. But I had lunch with my agent some weeks after the release, and the fact that the sentence that contained the word “failure” ended with “not your fault” didn’t prevent me from bursting into tears.

This is how publishing works: Each season publishers like Random House put out a number of books, each of which tends to fall into one of three categories: sure-fire bestsellers, like any book by Dan Brown or John Grisham; pretty good bets, like books by celebrities; and everything else. Publishers plan to spend a significant amount of money promoting all the books in the first two categories, but there simply isn’t enough money to commit firmly to supporting all the books in the third category. What happens, therefore, is that publishers give them all a little help so they can get off the ground. Then they wait to see which two or three catch on; once they’ve figured that out, they commit to supporting those two or three firmly, and perforce leave the rest to get by as best they can. As far as I can tell, the time a book has to catch on before the publisher has to stop paying attention to it is about six weeks. It’s hideous, of course, but it’s also exactly what I would do if I were a publishing company; given that the number of books published a year has more than doubled in the last seven years (from 135,000 in 2001 to 280,000 in 2008*), while the number of books bought a year has stayed more or less the same, I’m astonished that any company can do more than scrawl a book’s title on a Post-It and toss it out the window.

But now, back to our story. After I stopped crying, and finished a pint and a half of Häagen-Dazs Chocolate Peanut Butter Truffle ice cream, it became crystal clear what the problem was:

The title and the cover.

When the book was released and the reviews started coming in, I was delighted, because for the most part they were very favorable. But then I started to notice something, which was that almost every one said something along the lines of, “From the cover I thought this was going to be fluffy and shallow, but then I read it and I loved it.” Then people who had read the book started e-mailing me, and almost every one said something along the lines of, “From the cover I thought this was going to be fluffy and shallow, but then I read it and I loved it.”

The problem, it turned out, was that while many people saw the cover, thought the book was going to be fluffy and shallow, and bought it and read it anyway and loved it, they were far, far outnumbered by people who saw the cover, thought the book was going to be fluffy and shallow, and, since they weren’t interested in fluffy and shallow, went and bought something else (Backdraft: Fireman Erotica, one presumes).

(At least there were more people who bought it anyway and loved it, though, than people who bought it and then grew angry when it wasn’t fluffy and shallow. Seriously. A couple reviews were like, what is this? Where’s the Cher? There are hunky guys on the cover, why is he telling us about his dead mother?)

Now: I think the hardback cover is brilliant and beautiful. Since I know myself, I get a kick out of the disjunct between the cotton-candy outside of the book and the much richer chocolaty insides. Unfortunately, my editor and I forgot that the book-buying public did not know me. Seeing the unsubstantial outside, therefore, they assumed that book had an unsubstantial inside as well. It was awful. They were judging the book by its cover.

(There’s also of course the very real possibility that the reason people weren’t buying the book was that it was bad. But let’s assume this wasn’t the case, if only for the sake of discussion.)

So my publisher was about to do what was as I’ve said the only sensible thing: admit defeat, sell the paperback rights (which meant that they would at least make some of their money back), and move on.

Then I got a strange e-mail followed by a phone call from a Very, Very Famous Person, whom I can now reveal to have been Sir Elton John. He had read Swish, he said, and loved it. He said many other nice things about the book and offered to do whatever he could to help me out.

I e-mailed my editor with this information, naturally, and after a time got a reply containing the fabulous news that her boss thought they could use this as a sales hook, so they were going to go ahead and publish a paperback. Repackaged, with a new cover and a new subtitle. Naturally I celebrated by eating another pint and a half of Häagen-Dazs Chocolate Peanut Butter Truffle ice cream.

It took literally months to come up with the new cover and subtitle, but my editor’s assistant told me that I should see this as a good sign, because they wouldn’t spend so much energy on something they didn’t really believe in. (Then my editor got laid off—note, please that she had become my editor after my last editor had gotten laid off—but her assistant stayed, so I felt I could still trust her advice.)

So the paperback was released today. It’s called Swish: My Quest to Become the Gayest Person Ever and What Ended Up Happening Instead, it has a beautiful cover (click the image below to enlarge) that more clearly implies the material inside, and it’s graced with a foreword by Elton John. Of course I hope it will become a smash hit, but mostly I’m just grateful that the book has gotten a second chance.

*These statistics don’t include the 285,000 books self-published in 2008, which number represents an almost 500% increase from 2006.

June 15, 2009

The last thing my father needs is more stuff to put on shelves, so for his birthday last year my brother and I promised him a trip with us wherever he wanted to go. We finally made good this weekend, when the three of us went to Mississippi, the site of many of my father’s early triumphs.

We spent our first day in Jackson, where he and my mother lived in the late 60s working for the Lawyers’ Constitutional Defense Committee. The next day we went to Vicksburg, site of the 1863 siege that cut the South off from the Mississippi River, effectively winning the Civil War for the Union. Then we went up through the Mississippi Delta, where my father had argued his first civil rights cases.

Most of the small towns there seemed much better off, he said, than they had forty years before, but he was worried that the improvement had been achieved by the exodus of the poorest residents to cities like Chicago and Atlanta, and some of the small towns we saw, including one called Midnight, seemed to be just as badly off, he said, as they had been in the 1960s. I would post photographs, especially as I’d forgotten what rural poverty looks like, but the people weren’t showing off their penury for our entertainment, and the idea of taking pictures felt odd.

On our way back down to Jackson, we stopped in Indianola to visit the post office, which is at the center of the story of Minnie Cox, one of my favorite civil rights stories of all.

In 1903, the white citizens of Indianola decided they’d had enough of getting their mail from a black postmistress, so they ran Minnie Cox out of town, expecting President Theodore Roosevelt to give the post to a white person. He decided to deal with the situation a different way, however.

He just closed the post office.

And had Indianola’s mail rerouted—remember that nobody had cars yet—to the town of Greenwood, thirty miles away.

Eventually, after a year, during which he naturally kept paying Minnie Cox her salary, he appointed a new postmaster and reopened the Indianola post office; he then downgraded it from third class to fourth class because the year’s receipts had been so low.

Man, I love a good smackdown.

The post office can’t possibly be in the same place as it was over a century ago, but I was nonetheless thrilled to discover that Mrs. Cox has not been forgotten:

Now if only the rest of the state were as enlightened. . . .

June 14, 2009

Okay.

After a conversation with my dad, who as I’ve mentioned knows something about constitutional law, here’s how I’m really, really, really hoping the hideous Department of Justice brief supporting the Defense of Marriage Act happened.

1. The makeup of the current Supreme Court, which is where this suit would end up, pretty much guarantees that a constitutional challenge to DOMA would ultimately fail. If that happened, DOMA would be ruled constitutional, and there would be no way to get rid of it other than legislative repeal (very difficult) or a constitutional amendment (well nigh impossible). If the Obama administration really does want to kill DOMA, but is planning to wait until Obama has had a chance to appoint a few more liberal Supreme Court justices (which it’s very likely he’s going to be able to do), such a turn of events would be bad. Therefore, it wants to prevent Smelt v. United States from going to trial. This can happen only if the DOJ files a brief.

2. Now, the DOJ is essentially Congress’s lawyer. As such, it has a legal obligation not just to advocate on behalf of its client but to advocate as vigorously as it can on behalf of its client. It would be unethical for the DOJ to file a pro forma brief or one asking that the case be dismissed for lack of standing. So if they filed a brief at all (which they had to do—see above, “prevent Smelt v. United States from going to trial”) they really had to throw the kitchen sink in. They didn’t have to make it all so insulting and homophobic, but . . .

3. . . . we know the brief was written by W. Scott Simpson, a Bush holdover who was, as Andrew Sullivan points out, given an award by Alberto Gonzales for his defense of the Partial Birth Abortion Act. I believe that it’s reasonable to assume he is not the LGBT community’s best friend.

4. It would be great if he were the highest-ranking DOJ official on the brief, because apparently none of the highest-ups at the DOJ pay attention to briefs filed in district court cases (i.e., lower-than-Supreme-Court cases). Unfortunately he’s not; the highest-ranking DOJ official on the brief is Tony West, the Assistant Attorney General in the Civil Department. So what I’m really, really, really hoping is that Tony West is an idiot and that, when he saw a hideous brief written by a bigot, he idiotically didn’t realize that as a brief on such a high-profile issue it ought to be checked with extreme caution, and he also idiotically didn’t realize he ought to give Lambda Legal, the ACLU, and other gay legal organizations a heads-up beforehand, and idiotically just filed the damn thing.

5. Tony West is at this very moment being reamed a new and extraordinarily painful asshole by many, many, many very, very important people, and a number of other very, very important people are trying to figure out how to clean up the mess he made.

6. (Also, apparently, the people in the DOJ’s Civil Department are widely known to be clumsy fuck-ups whose blunders the DOJ’s Civil Rights Department—not the same—often have to fix.)

So I’m really, really, really hoping that’s how it happened. Because if it’s not, I’m not sure how to escape the conclusion that I voted for a liar.

Even if that is how it happened—which I truly do believe is possible—at this moment I feel that Obama has just used up the last bit of LGBT slack I’ve been willing to cut him.